Free at Last

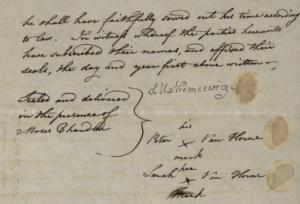

Manumission Document

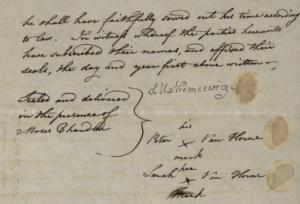

Manumission Document

New Jersey has a long and complicated history with slavery. According to the country’s first census in 1790, over 11,000 enslaved individuals lived in the state. In 1796, the New Jersey Legislature banned the import of enslaved people into the state and wrote rules to expedite the manumission process. Manumission was an 18th-century ideal where enslaved people were freed upon the condition that they remain in service to those who had claimed ownership of them. Then, in 1804, New Jersey passed a law providing for the “gradual emancipation of slaves,” which stated that, “every child born of a slave . . . after the fourth day of July next, shall be free; but shall remain the servant of the owner of his or her mother . . . if a male, until the age of twenty-five years, and if a female until the age of twenty-one years.” Thus, New Jersey became the last Northern state to begin the process of state-wide emancipation. As a result, the number of free African Americans in New Jersey grew from 4,000 in 1800 to 18,000 in 1830, while the number of enslaved people fell from 12,000 to 2,000. This document, dated May 2, 1829, manumitted two enslaved individuals,, Peter Van Horne and his wife, Sarah, who had lived and worked at Liberty Hall for Susan (Livingston) [Kean] Niemcewicz. The Van Hornes were illiterate and so signed the document with their marks. Although freed, they agreed to continue to serve Mrs. Niemcewicz for a hundred dollars a year. Both Sarah and Peter are buried in the First Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth. On Loan from the Special Collections Research Library and Archive, Kean University.