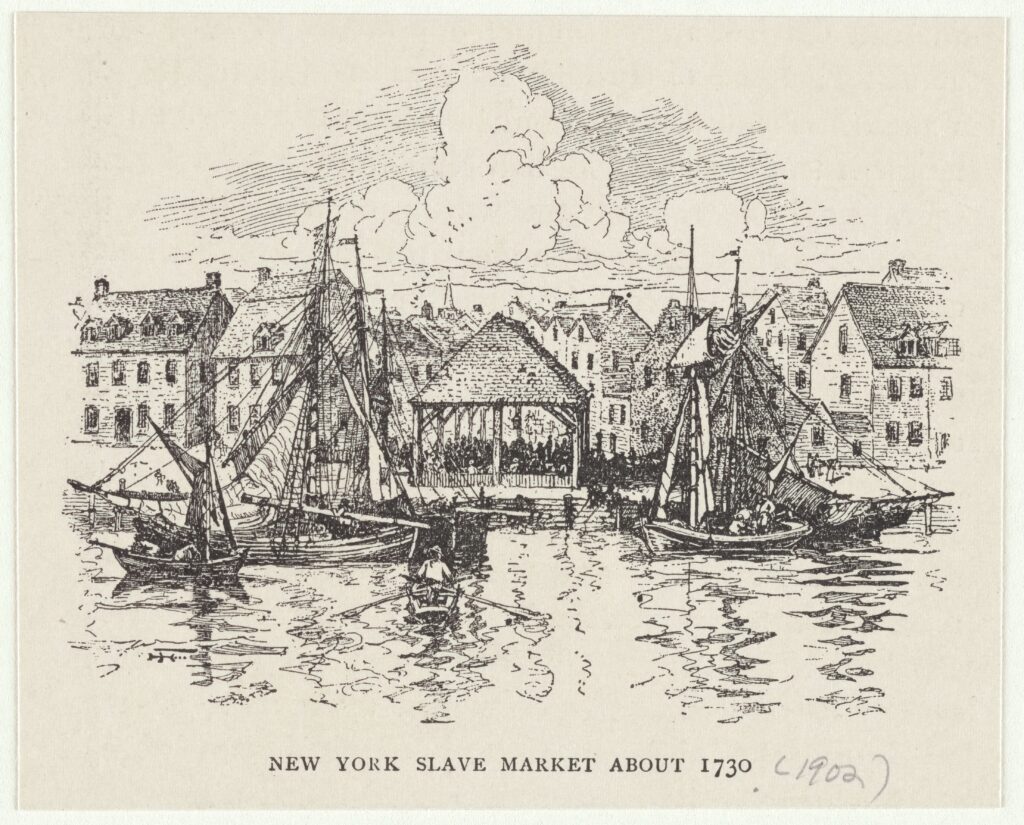

The institution of slavery was a part of Liberty Hall’s history from its very beginning. Enslaved people were made to live and work at Liberty Hall from at least 1774, when William Livingston and his family brought several individuals to this house and farm from New York, until 1829 when Susan (Livingston) [Kean] Niemcewicz manumitted (or freed) Peter and Sarah Van Horne, the last people she enslaved in New Jersey. Even after there were no longer any people enslaved at Liberty Hall, the legacy of slavery continued to impact life on the site, as free and formerly enslaved Black people labored here through 1840.

It is unclear exactly how many people were enslaved here over these fifty-five years, nor do we know for certain exactly how many of Liberty Hall’s white residents claimed ownership over enslaved people. What is known, however, is the fact that over twenty-five enslaved people lived, worked and raised families at Liberty Hall, as they navigated the complexities of institutional slavery in New Jersey.