Enslaved people’s lives and choices were constrained by political and economic developments largely outside of their control. Those enslaved at Liberty Hall, as in the rest of New Jersey, were forced to work within oppressive systems in order to retain any agency, security, and comprot for themselves and their families. Although their everyday activities were dictated by the people who claimed ownership over them, the world outside of Liberty Hall’s boundaries also impacted the lives of the people enslaved here.

Enslavement at Liberty Hall: What Did Their World Look Like?

The Law

New Jersey’s laws supported and condoned slavery in both the colonial period and Early Republic. The Dutch first brought enslaved people to New Jersey in 1726, but the english used policy to encourage and grow the institution of slavery when they took over the colony later in the seventeenth century Beginning in 1664, New Jersey’s colonial government granted land to settlers who claimed ownership over enslaved people and passed laws that controlled and restricted the behavior of enslaved and free Black people. Colonists brought enslaved people to all areas of New Jersey, but far more enslaved people lived in the eastern part of the colony, especially Bergen County, where slavery was more profitable. Land grants encouraged New Jersey’s white citizens to use enslaved people’s labor for farming, but enslaved people were also made to work on the colony’s docks, in stores or workshops, in mines, and inside of homes. William LIvingston lived too late to benefit from colonial land grants by the time he came to Liberty Hall, but he still took advantage of enslaved people’s labor on his farm, relying on Henry and other Black men to tend to Liberty Hall’s harvests and other farm labor.

Enslaved and free Black people lived with heavy restrictions, imposed by both their individual enslavers and the government. These laws, called “slave codes” aimed to isolate Black communities and make upward mobility difficult for those who gained their freedom. In 1704, New Jersey passed its first “slave code,” which imposed curfews on Black people, made it illegal for free and enslaved Black people to own property, banned enslaved people from selling goods, and forced enslaved people to remain within ten miles of the homes of the people who claimed ownership over them, with whipping as a punishment for disobedience. Enslaved people from other colonies also faced legalized violence if they were discovered in New Jersey without written permission from their enslavers. Not only were enslaved people subjected to violence from their enslavers, the government imposed additional restrictions on their behavior and these laws were backed up by force.

Resistance

Enslaved people, like those at Liberty Hall, did not accept their oppression without resistance. They used several methods, both large and small, to regain a degree of control over their lives, some of which might not be recognizable as resistance at first glance. One of the most obvious types of resistance was armed revolt. This was both rare and extremely dangerous, but although violence was not typical, it factored heavily in enslavers’ collective imaginations. Their largely unjustified fear of armed revolt, as well as their understanding of the potential power of enslaved people’s united resistance resulted in far more restrictive laws governing Black people’s freedoms and violent retribution against any suspected uprising.

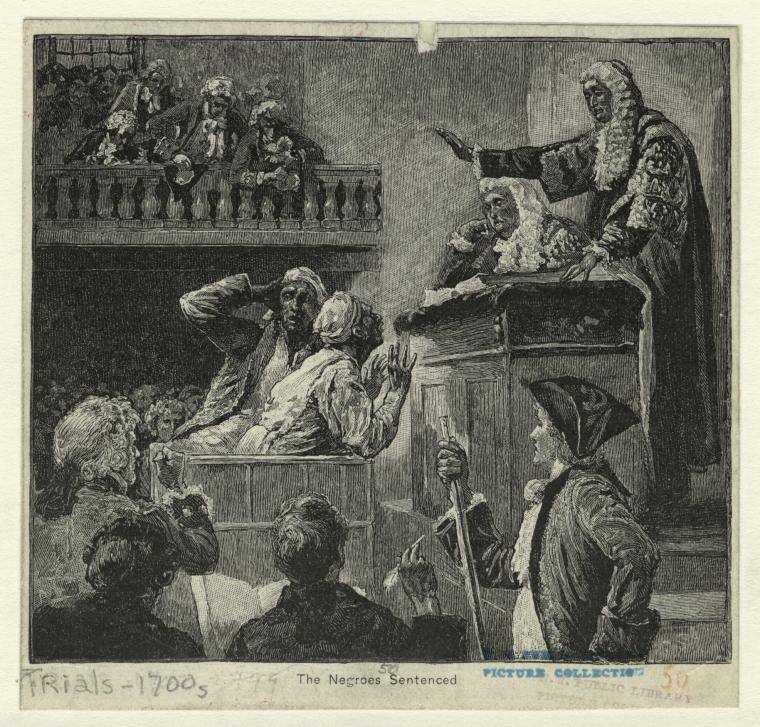

There were, however, some instances where enslaved people did use violence to resist enslavement, including one revolt in New York City that had a particular impact of the lives of those enslaved in New Jersey. In 1712, a group of twenty-three enslaved New Yorkers armed themselves and came together to fight for their freedom but failed and seventy Black New Yorkers were arrested and twenty-one were executed. The colonial government in New Jersey responded to this revolt by further restricting Black people’s freedoms. Fearful of the power of united action amongst enslaved people and especially the power of free (and thus unmonitored and uncontrolled) Black communities, the colony made manumission prohibitively expensive.

Paranoia about enslaved people’s resistance reemerged in 1741, when white New Yorkers believed that a series of fires in the city were the work of enslaved individuals. The city responded to these fears and assumptions by executing thirty Black and four white people and selling eighty-four Black people to the Caribbean without any proof of involvement. Black New Jerseyans did not escape this paranoia and three Black people were burned at the stake in Elizabethtown.

Although these events took place long before anyone was enslaved at Liberty Hall, they informed the society in which Black New Jerseyans lived, from the laws passed to discourage resistance and unity, to the actions taken by individual enslavers to isolate and control the people over whom they claimed ownership.

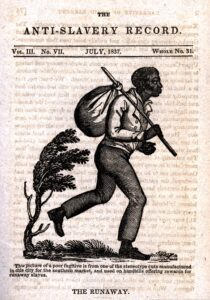

There were many other ways that people resisted enslavement without violence, and self-emancipation was one such method. New Jersey newspapers are full of “runaway ads” that described individuals who escaped from slavery and offered rewards for their capture. Henry, a man enslaved by William Livingston at Liberty Hall, escaped from the farm right before the planting season in 1786 and was likely successful in his self-emancipation. Not only was his decision to escape Liberty Hall an act of resistance, but leaving at a time when Livingston most needed farm workers may also have been a way to punish Livingston and demonstrate his personal agency. Livingston did not see it this way. Instead, he described Henry as lazy, and viewed his escape as an attempt to avoid hard work. Livingston was either unable or unwilling to acknowledge the risks that Henry took in order to seek his freedom.

Enslaved people could protect themselves to some extent by using more subtle forms of resistance, including working slowly, breaking objects, producing poor quality products, pretending to be ill, or stealing. White people like Livingston often misinterpreted these actions as laziness, not realizing that they were actually deeply political actions. Before self-emancipating, Henry stole oats and eggs from the farm, both harming Livingston financially and preparing for his escape. Smaller, more subtle, methods of resistance like this allowed enslaved people to reclaim some control over their lives and were more difficult for enslavers to punish.

Family

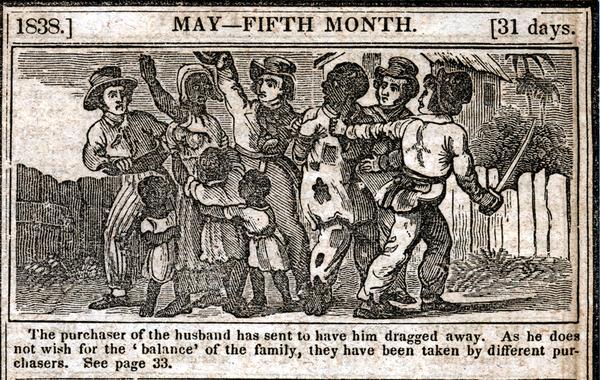

Enslaved people found comfort in relationships with their families and communities, but they were aware that they might be separated from the people they loved at any time. They had no control over where they or their family members might be taken or to whom they might be sold. When separated, they could only learn about their loved ones if white people were willing to pass along questions and messages in letters. Abbe, who was brought to France by Sarah (Livingston) Jay, was deeply concerned about her family at or near Liberty Hall, especially her husband, but we only know about love and worry for her family because Jay relayed these concerns in a letter to her sister.

There were other ways that enslavement divided families. Sometimes husbands and fathers were enslaved at different locations than their wives and children and required permission from their enslavers to visit their families. This was likely common in New Jersey because individual enslavers generally claimed ownership over fewer enslaved people than in the South. We do not know how many families were separated this way at Liberty Hall, but there were several women and children who were enslaved here whose husbands and fathers are not listed on any records alongside them, possibly indicating that they were enslaved elsewhere. This is most noticeable in the birth records for children born after New Jersey passed its gradual emancipation law. The Keans recorded the births of these technically free children and the identities of their enslaved mothers, but not their fathers. It is difficult to know where the fathers of these children were enslaved, if they were enslaved at all.

The institution of slavery also complicated family relationships for free Black New Jerseyans. In addition to free fathers having no rights over their enslaved children, New Jersey’s laws banning free Black people from entering the state made family reunification impossible for free Black people whose family members were enslaved in New Jersey. Even children born free after New Jersey’s gradual emancipation law was passed could be taken away from their enslaved mothers and abandoned to the state.

Revolution

Although the American Revolution professed the ideals of freedom and liberty, this did not extend to all, including enslaved people. William Livingston and many other founders knew that slavery was wrong but nevertheless continued to enslave people. As revolutionary governor of New Jersey, Livingston asked the state legislature to work towards gradual abolition, but he was willing to take back this request to prioritize the war effort. Livingston requested the legislature to consider gradual abolition again in 1785, but they refused, this time claiming that New Jersey needed to recover economically from the war. The institution of slavery expanded in the eastern part of the state following the Revolution, as white New Jerseyans used enslaved people’s labor to rebuild the state’s economy and make up for the shortage of white farm workers. Like many white New Jerseyans, Livingston continued to rely upon enslaved laborers at his farm and house in the years after the Revolution, including Henry, Bell, Lambert, and others.

Despite this, there were some anti-slavery victories in New Jersey in the aftermath of the Revolution. In 1786, the state legislature made it illegal to import enslaved people into New Jersey from outside of the country (although the interstate trade in enslaved individuals continued to break up families). The state government also made it less expensive to manumit enslaved people between the ages of 21 and 35 (later 40), making freedom achievable for more Black people, and banned the abuse of enslaved people, although this was difficult to enforce. At the same time, free Black people from elsewhere in the United States were prohibited from entering New Jersey and free Black New Jerseyans needed extensive documentation to leave the state. William Livingston’s choice in 1787 to manumit Bell and Lambert, an enslaved mother and child, was almost certainly directly related to these changing laws, which allowed him to free both without any financial consequences.

Activism

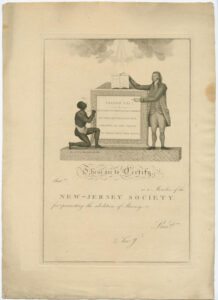

Outside of Quaker communities in the western portion of the state, anti-slavery agitation in New Jersey was both slow to emerge and less active than elsewhere in the north. By 1793, New Jerseyans founded the short-lived New Jersey Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and in 1804, the state passed a law for gradual emancipation (the last in the North to do so). This law was far more concerned with the property rights of enslavers than enslaved people’s freedom, however. Because it ruled that any child born to an enslaved mother after July 4, 1804, would be free after the age of 25 (for men) and 21 (for women), not only did this law not free anyone, but it also allowed enslavers to continue to profit from the labor of children and young people who were technically free. These children included Robert Van Horne, Stephen, and Abraham, who grew up at Liberty Hall .

The relationship between New Jersey and the institution of slavery did not end with gradual emancipation. Even though the state passed a law entitled “An Act to Abolish Slavery” in 1846, this also did not free enslaved people from forced labor. It instead reclassified them as “apprentices for life.” This change in language did nothing to improve the lives of Black people and by the time of the Civil War, there were still several functionally enslaved people living in New Jersey who were only freed with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

After gradual emancipation, free Black people in New Jersey were still subject to constant monitoring and policing, largely due to white fear of uncontrolled Black communities. You can see one example of this in Elizabethtown, when white residents, including Liberty Hall’s Peter Kean, organized a fundraising campaign in 1811 to build a jail that would counteract what they described as the “growing evil” of “the disorderly conduct of the Negroes.” White fear and policing of Black bodies such as this was rooted in the institution of slavery and the exploitation of Black communities.